In schools and in any situation where we work with youth to help them develop the skills necessary to function in life there is a glitch in the system. The glitch is moving from what we know they should be able to do and moving away from sticking the current modes of operation.

Recently, my son had an open note test. First, congratulations to the teacher for making this happen. Finally, a chance where students realized that simply memorizing facts is not the answer to demonstrating how “smart” you are. Congratulations for making the students use skills needed in this Google aged era where textbook information is readily available day and night.

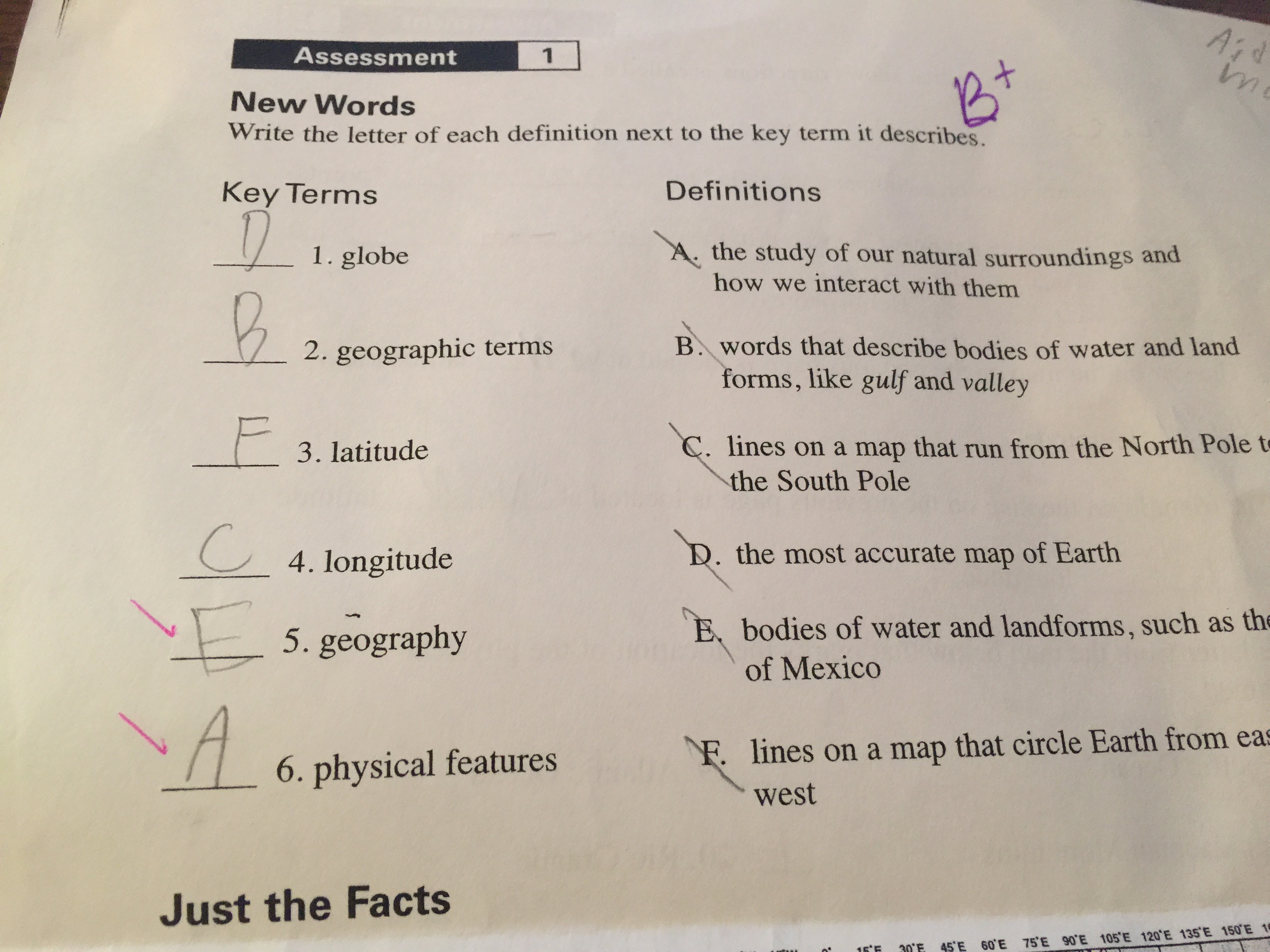

When my son brought the test home I noticed he missed two in the matching section. I was floored to be honest. How could he miss these? I mean, he had the book right there to use during the test. Needless to say, I was not happy(yes, you can challenge my parenting all you want). I talked to him about it and he was not sure what happened. I honestly believe him because had he known the problem then the problem would not have happened.

“If I don’t know I don’t know, I think I know. If I don’t know I know, I think I don’t know.” — R.D. Laing

I let this go.

The next week my son had to do some “research” for our robotics team. I coach a First LEGO League team. We told the students to go home and research all they could about a trash item. I sat down with my son and showed him a few things on how to search. I then watched him process the information. I was once again floored.

He had no idea how to make sense of the article.

Now, my son is intelligent. He is a very bright young man that I love more and more every single day, but I was watching before my very eyes a need for educational reform. A change in education that I need to be part of and need to work on how I teach myself.

When my son was viewing the screen here is what he did.

- He wanted to click on images right away in Google. I asked him why and he said it would be easier to find information through a chart or an image that was interesting. Information overload

- When I told him no to that idea and showed him how to read under the link title, he clicked the article. The first thing he did was scroll at a furious pace. He did not read a word. He was once again looking for images. Information Overload

- He had no clue how to process what he was reading. He was clueless how to take information to form an argument with all the distractions on the page. The page was too busy and just messed with his mind thinking it was too hard to do the task. Information overload!

- He was distracted by all that the internet has to offer. Information overload

What are we doing in schools to help with this? I have witnessed over the years packets and packets of fill in the blank, worksheets catered to specific items, and finding answers that have no meaning nor show any comprehension of the reading. I have witnessed zero/minimal teaching taking place teaching students how to process information. We simply tell them to “research”. No wonder kids hate it. What does this word mean? What do we do? How do we do it? Do we give students time in class to practice? Do we give them time in class to read online instead of a textbook with a packet? Quizzing my kids for a test and they know the “correct” answer to the study guide, but when pressed to explain why or the reasons for the answer they have no idea. The common response is often, “I don’t know dad, my teacher told me to write these words down and that is what I did!”

Watching my son mix up words in a textbook and not know how to research made me realize that we have not shifted our practices much. We know students need to be able to do these things. I doubt anyone would disagree. However, how many of us have changed our approach? I know I was caught red handed as a coach to robotics that I have not adapted my teaching(and I also know as a teacher I did the same). We often assume they know how to do these things. I think we assume that WE as educators know how to do these things. I would take it a step further and say that we as educators need to be taught how to teach these skills before we are expected to teach students. The transition from myself as a student to adult has also seen the transition from limited knowledge of what the local library contained in the card index to any information I want when I want it. I know as a parent I still expect old school techniques to appear in the backpacks of my kids because that is what I am used to. I know as a parent I sometimes just want that fill in the blank(even though there is zero learning taking place) because it is easy to get it done.

But, we are just wasting precious time to not prepare these students for independent skill development if we don’t teach and nurture these skills.

I know that we know what we need to do to help students, but the question is why don’t we change our own practice to make it happen?

It reminds me of a quote from Jack Welch,

“If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, then end is near.”

My solution?

1. Move into action. I will be creating lessons and videos helping student learn how to conduct research for robotics. We have already shifted our method of robotic problem solving from just talking about ideas to following the computational thinking process.

2. I will be doing my own research and creating tutorials and tips to help those who don’t have time to do it all. Teaching is already too busy to think about adding one more thing.

We owe it to ourselves and we it owe it to our students.

I think you brought up some great questions and ideas here. I also think #2 in your solution section is spot-on. I believe many teachers want to implement these kinds of changes, but time is a road block. We need more time to implement new ideas and change, to collaborate with others, etc. I also sometimes think that class activities/teaching philosophies have changed a great deal for many educators, but the “proof” of the learning (assignments/assessments), in many instances, has not kept up with the changes.